Les astronomes ont repéré des signes d’un « point chaud » en orbite autour de Sagittarius A*, le trou noir au centre de notre galaxie.

Les astronomes ont repéré des signes d’un « point chaud » en orbite autour de Sagittarius A*, et[{ » attribute= » »>black hole at the center of our galaxy, using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA). The finding helps us better understand the enigmatic and dynamic environment of our supermassive black hole.

“We think we’re looking at a hot bubble of gas zipping around Sagittarius A* on an orbit similar in size to that of the planet Mercury, but making a full loop in just around 70 minutes. This requires a mind-blowing velocity of about 30% of the speed of light!” says Maciek Wielgus of the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn, Germany. He led the study that was published today (September 22, 2022) in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

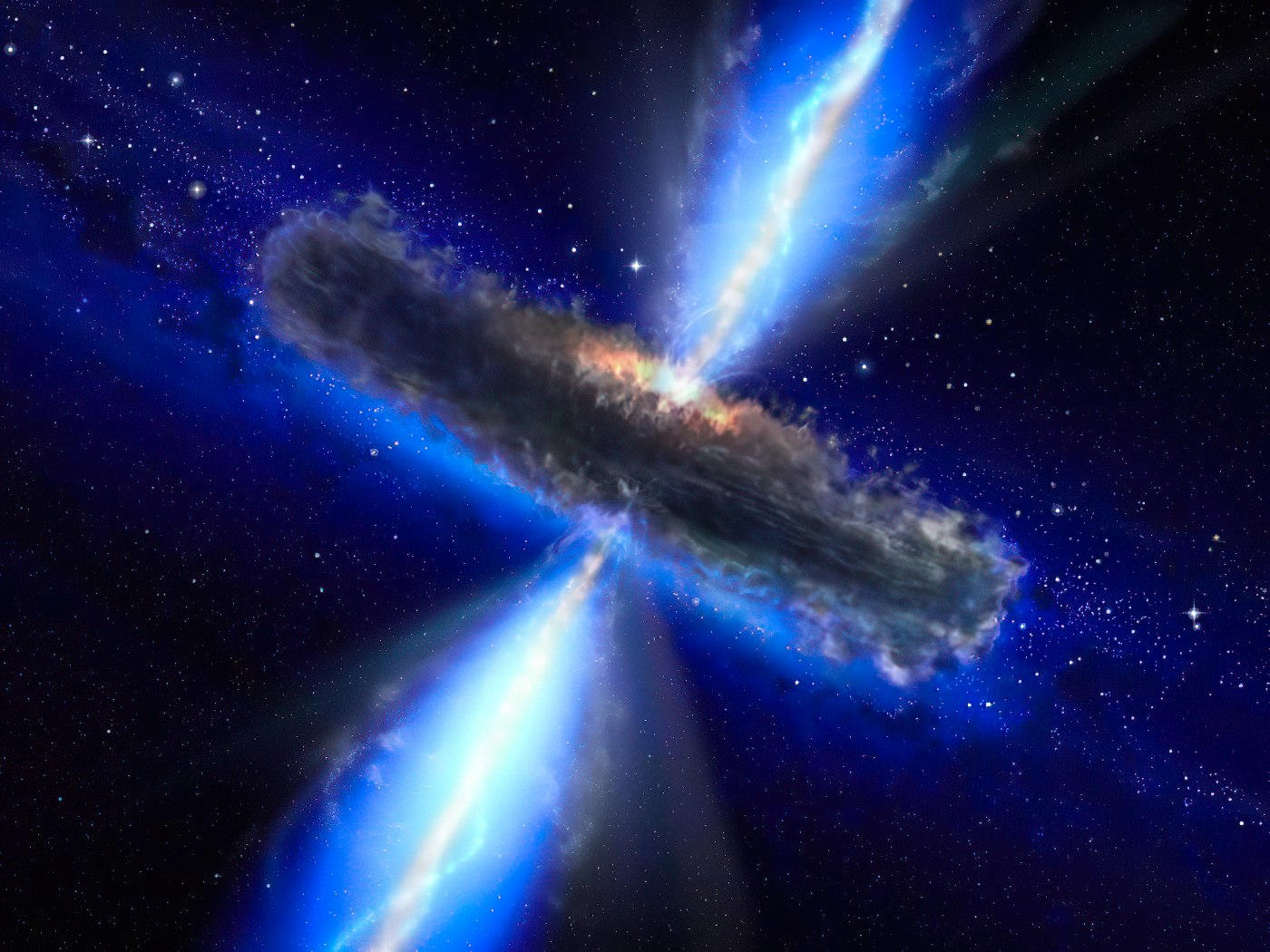

This shows a still image of the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A*, as seen by the Event Horizon Collaboration (EHT), with an artist’s illustration indicating where the modeling of the ALMA data predicts the hot spot to be and its orbit around the black hole. Credit: EHT Collaboration, ESO/M. Kornmesser (Acknowledgment: M. Wielgus)

The observations were made with ALMA in the Chilean Andes, during a campaign by the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) Collaboration to image black holes. ALMA is — a radio telescope co-owned by the European Southern Observatory (ESO). In April 2017 the EHT linked together eight existing radio telescopes worldwide, including ALMA, resulting in the recently released first-ever image of Sagittarius A*. To calibrate the EHT data, Wielgus and his colleagues, who are members of the EHT Collaboration, used ALMA data recorded simultaneously with the EHT observations of Sagittarius A*. To the research team’s surprise, there were more clues to the nature of the black hole hidden in the ALMA-only measurements.

Grâce à ALMA, les astronomes ont trouvé une bulle de gaz chaude en orbite autour de Sagittarius A*, le trou noir au centre de notre galaxie, à 30 % de la vitesse de la lumière.

Par hasard, certaines observations ont été faites peu de temps après qu’une explosion ou une lueur d’énergie de rayons X ait été émise depuis le centre de notre galaxie, qui a été observée par[{ » attribute= » »>NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory. These kinds of flares, previously observed with X-ray and infrared telescopes, are thought to be associated with so-called ‘hot spots’, hot gas bubbles that orbit very fast and close to the black hole.

“What is really new and interesting is that such flares were so far only clearly present in X-ray and infrared observations of Sagittarius A*. Here we see for the first time a very strong indication that orbiting hot spots are also present in radio observations,” says Wielgus, who is also affiliated with the Nicolaus Copernicus Astronomical Center, in Warsaw, Poland and the Black Hole Initiative at Harvard University, USA.

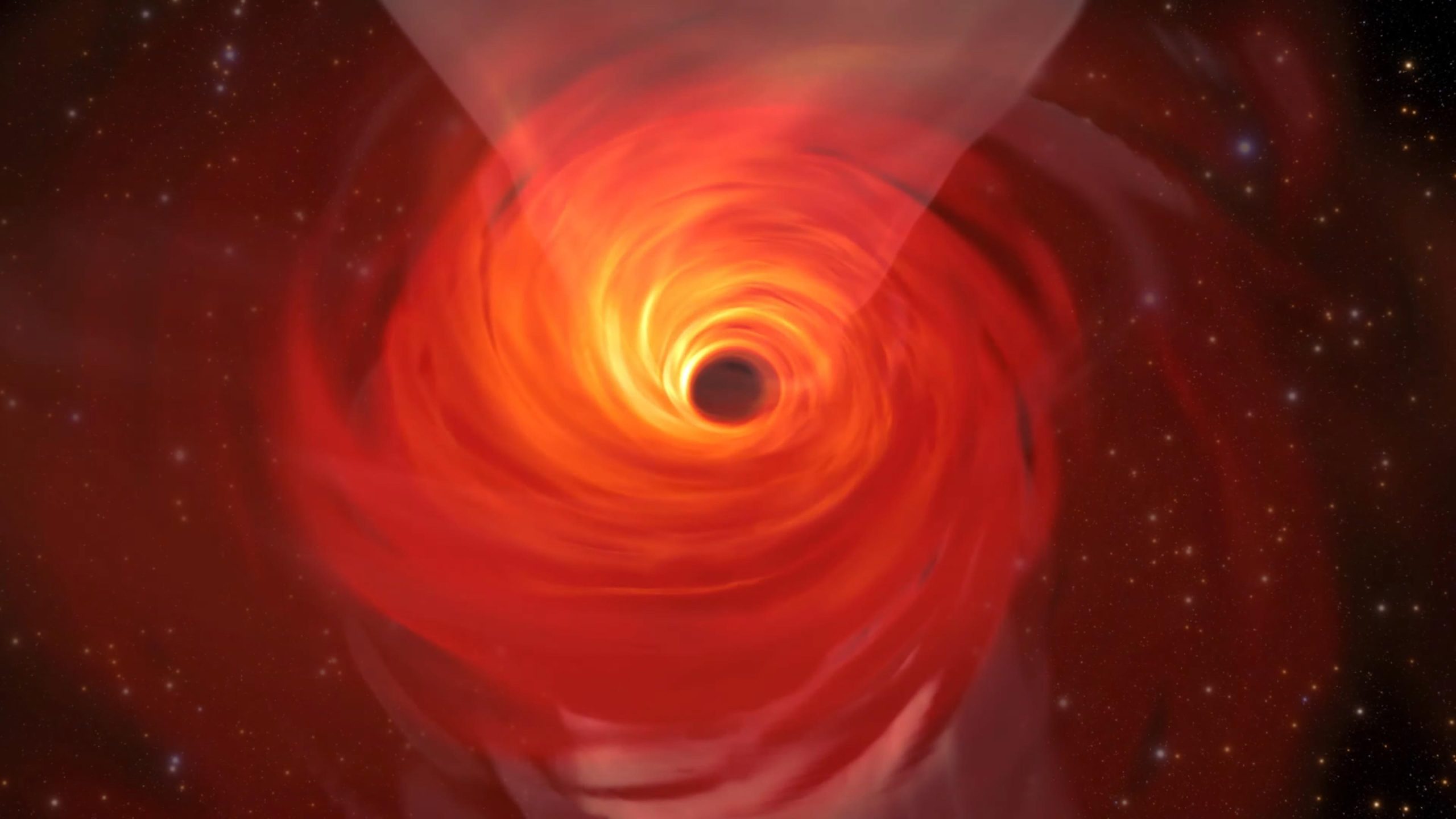

Cette vidéo montre une animation d’un point chaud, une bulle de gaz chaud, en orbite autour du Sagittaire A*, un trou noir quatre millions de fois plus grand que notre Soleil au centre de notre planète.[{ » attribute= » »>Milky Way. While the black hole (center) has been directly imaged with the Event Horizon Telescope, the gas bubble represented around it has not: its orbit and velocity are inferred from both observations and models. The team who discovered evidence for this hot spot — using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), in which ESO is a partner — predicts the gas bubble orbits very close to the black hole, at a distance about five times larger than the black hole’s boundary or “event horizon.”

The astronomers behind the discovery also predict that the hot spot becomes dimmer and brighter as it goes around the black hole, as indicated in this animation. Additionally, they can infer that it takes 70 minutes for the gas bubble to complete an orbit, putting its velocity at an astonishing 30% of the speed of light.

Credit: EHT Collaboration, ESO/L. Calçada (Acknowledgment: M. Wielgus)

“Perhaps these hot spots detected at infrared wavelengths are a manifestation of the same physical phenomenon: as infrared-emitting hot spots cool down, they become visible at longer wavelengths, like the ones observed by ALMA and the EHT,” adds Jesse Vos. He is a PhD student at Radboud University, the Netherlands, and was also involved in this study.

The flares were long thought to originate from magnetic interactions in the very hot gas orbiting very close to Sagittarius A*, and the new findings support this idea. “Now we find strong evidence for a magnetic origin of these flares and our observations give us a clue about the geometry of the process. The new data are extremely helpful for building a theoretical interpretation of these events,” says co-author Monika Moscibrodzka from Radboud University.

This is the first image of Sgr A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy. It’s the first direct visual evidence of the presence of this black hole. It was captured by the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), an array that linked together eight existing radio observatories across the planet to form a single “Earth-sized” virtual telescope. The telescope is named after the event horizon, the boundary of the black hole beyond which no light can escape. Credit: EHT Collaboration

ALMA allows astronomers to study polarized radio emission from Sagittarius A*, which can be used to unveil the black hole’s magnetic field. The team used these observations together with theoretical models to learn more about the formation of the hot spot and the environment it is embedded in, including the magnetic field around Sagittarius A*. Their research provides stronger constraints on the shape of this magnetic field than previous observations, helping astronomers uncover the nature of our black hole and its surroundings.

This image shows the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) looking up at the Milky Way as well as the location of Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galactic center. Highlighted in the box is the image of Sagittarius A* taken by the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) Collaboration. Located in the Atacama Desert in Chile, ALMA is the most sensitive of all the observatories in the EHT array, and ESO is a co-owner of ALMA on behalf of its European Member States. Credit: ESO/José Francisco Salgado (josefrancisco.org), EHT Collaboration

The observations confirm some of the previous discoveries made by the GRAVITY instrument at ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT), which observes in the infrared. The data from GRAVITY and ALMA both suggest the flare originates in a clump of gas swirling around the black hole at about 30% of the speed of light in a clockwise direction in the sky, with the orbit of the hot spot being nearly face-on.

“In the future, we should be able to track hot spots across frequencies using coordinated multiwavelength observations with both GRAVITY and ALMA — the success of such an endeavor would be a true milestone for our understanding of the physics of flares in the Galactic center,” says Ivan Marti-Vidal of the University of València in Spain, co-author of the study.

Wide-field view of the center of the Milky Way. This visible light wide-field view shows the rich star clouds in the constellation of Sagittarius (the Archer) in the direction of the center of our Milky Way galaxy. The entire image is filled with vast numbers of stars — but far more remain hidden behind clouds of dust and are only revealed in infrared images. This view was created from photographs in red and blue light and forming part of the Digitized Sky Survey 2. The field of view is approximately 3.5 degrees x 3.6 degrees. Credit: ESO and Digitized Sky Survey 2. Acknowledgment: Davide De Martin and S. Guisard (www.eso.org/~sguisard)

The team is also hoping to be able to directly observe the orbiting gas clumps with the EHT, to probe ever closer to the black hole and learn more about it. “Hopefully, one day, we will be comfortable saying that we ‘know’ what is going on in Sagittarius A*,” Wielgus concludes.

More information

Reference: “Orbital motion near Sagittarius A* – Constraints from polarimetric ALMA observations” by M. Wielgus, M. Moscibrodzka, J. Vos, Z. Gelles, I. Martí-Vidal, J. Farah, N. Marchili, C. Goddi and H. Messias, 22 September 2022, Astronomy & Astrophysics.

DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202244493

The team is composed of M. Wielgus (Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie, Germany [MPIfR]; Centre astronomique Nicholas Copernicus, Académie polonaise des sciences, Pologne; The Black Hole Initiative à l’Université de Harvard, États-Unis [BHI]), M. Moscibrodzka (Département d’Astrophysique, Université Radboud, Pays-Bas [Radboud]), J. Vos (Radboud), Z. Gelles (Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, USA et BHI), I. Martí-Vidal (Universitat de València, Espagne), J. Farah (Las Cumbres Observatory, USA; Université de Californie, Santa Barbara, États-Unis), N. Marchili (Centre régional italien ALMA, INAF-Istituto di Radioastronomia, Italie et MPIfR), C. Goddi (Dipartimento di Fisica, Università degli Studi di Cagliari, Italie et Universidade de São Paulo, Brésil) et H. Messias (Observatoire conjoint ALMA, Chili).

L’Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), une installation internationale d’astronomie, est un partenariat entre l’ESO, la National Science Foundation (NSF) des États-Unis et les Instituts nationaux des sciences naturelles (NINS) du Japon, en collaboration avec la République du Chili. ALMA est financé par l’ESO au nom de ses États membres, par la NSF en collaboration avec le Conseil national de recherches du Canada (CNRC) et le ministère de la Science et de la Technologie (MOST) et par le NINS en collaboration avec l’Academia Sinica (AS) à Taïwan et l’Institut coréen d’astronomie et des sciences spatiales (KASI). ). La création et les opérations d’ALMA sont dirigées par l’ESO au nom de ses États membres ; Par le National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO), exploité par Associated Universities, Inc. (AUI), au nom de l’Amérique du Nord ; Et par l’Observatoire astronomique national du Japon (NAOJ) pour le compte de l’Asie de l’Est. L’Observatoire conjoint d’ALMA (JAO) fournit un leadership et une gestion unifiés pour la construction, l’exploitation et l’exploitation d’ALMA.

L’Observatoire européen austral (ESO) permet aux scientifiques du monde entier de découvrir les secrets de l’univers pour le bénéfice de tous. Nous concevons, construisons et exploitons des observatoires de classe mondiale sur Terre – que les astronomes utilisent pour aborder des questions passionnantes et diffuser la magie de l’astronomie – et promouvons la coopération internationale en astronomie. Fondée en tant qu’organisation intergouvernementale en 1962, l’ESO soutient aujourd’hui 16 États membres (Autriche, Belgique, République tchèque, Danemark, France, Finlande, Allemagne, Irlande, Italie, Pays-Bas, Pologne, Portugal, Espagne, Suède, Suisse et Royaume-Uni ), En collaboration avec le pays hôte, le Chili, et avec l’Australie en tant que partenaire stratégique. Le siège social de l’ESO, centre d’accueil et planétarium, ESO Supernova, est situé près de Munich en Allemagne, tandis que le désert chilien d’Atacama, un endroit merveilleux avec des conditions uniques pour observer le ciel, accueille nos télescopes. L’ESO exploite trois sites de surveillance : La Silla, Paranal et Chajnantor. À Paranal, l’ESO exploite le Very Large Telescope et son Interféromètre Very Large Telescope, ainsi que deux télescopes infrarouges et le télescope visible VLT. Toujours à Paranal, l’ESO hébergera et exploitera le télescope South Array Cherenkov, l’observatoire de rayons gamma le plus grand et le plus sensible au monde. En collaboration avec des partenaires internationaux, l’ESO exploite APEX et ALMA à Chajnantor, deux installations de surveillance du ciel millimétriques et submillimétriques. À Cerro Armazones, près de Paranal, nous construisons le « plus grand œil du monde sur le ciel » – le très grand télescope de l’ESO. Depuis nos bureaux de Santiago, au Chili, nous soutenons nos opérations dans le pays et travaillons avec des partenaires et la communauté chilienne.

![Les bundles PS5 et Xbox Series X sont disponibles sur GameStop [UPDATE: Sold Out]](https://cdn.vox-cdn.com/thumbor/TRNOGkwP-9WJo6OJdB0e-EeFdk8=/0x146:2040x1214/fit-in/1200x630/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21990372/vpavic_4261_20201023_0068.jpg)